Introduction

Within This Page

Successful site security design is challenging. In part, this is because key phases – e.g., risk assessments, design concepts, funding and construction – are undertaken by different actors over a long period of time. Moreover, necessary countermeasures are often resource intensive, decision making may be fraught with emotional context, and multiple project purposes may be hard to reconcile. This makes security projects especially process dependent.

A careful and calculated process ensures that security concerns receive early and informed consideration and are integrated throughout planning, design, and construction. Such a process puts the Project Team in a strong position to achieve effective risk reduction while meeting budget, schedule, and public space design objectives.

Effective Site Security Design addresses the underlying principles that guide every security design project and the elements and tools available to the designer. This Resource Page describes how to apply these principles and tools. A hypothetical test case is included which illustrates the recommended process.

The process discussion includes detailed descriptions of the unique nature of security decision-making, how security decisions fit into the capital funding process, the roles and responsibilities of Project Team members, and the principles that guide the entire site security design process.

The hallmarks that must form the foundation of a successful and well-balanced security project:

- Strategic Reduction of Risk

- Comprehensive Site Design

- Collaborative Participation

- Long-Term Development Strategy

At every stage of the process, team members are expected to consider identified risks, operational requirements, and local impacts, to balance safety with cost, aesthetics, public use, and accessibility. Although each person on the Project Team brings unique technical skills, perspectives, and interests to the table, everyone should understand each of the hallmarks and their role in achieving them.

Creative problem solving—and successful projects—are the result when Project Team members share the responsibility to achieve each and every hallmark: when the blast expert understands how his or her recommendations affect comprehensive site design strategies, when the designer understands how his or her scheme supports long-term development of the area, and when the community stakeholder understands how his or her actions can support risk reduction at the federal facility.

Rich architectural detailing, formal entry, and minimal setback are characteristics common to many urban historic federal buildings. Credit: The Site Security Design Guide, GSA

Overview of the Site Security Design Process

Successful site security design comprises eight phases, each an important step toward a design that exceeds the hallmarks of a great project. These phases are summarized below:

Phase 1. Project Start focuses on the roles and responsibilities of the Project Team, communication and information sharing, and the decision-making process. The team begins this stage with a sound understanding of the completed risk assessment and its outputs.

- Coordinate site security design with the existing project development processes for large and small projects

- Consider previous building risk assessments and recommendations within the context of the present project and all objectives, including both security and design

- Carefully choose team members based on project needs and promote open channels of communication across specialties

Risk Assessments and Security Recommendations

Department of Homeland Security's (DHS) Federal Protective Service is responsible for conducting risk assessments of all federal buildings on a regular basis. DHS conducts its risk assessment based upon the actual or perceived threat to the building (the events that must be defended against), the vulnerability of that building (the susceptibility to the threat), the consequences if an event should occur, and the probability of that event based upon a variety of factors. Then, with stakeholder input, DHS provides a final report with recommended countermeasures.

Depending on the nature of the project, the detailed security analysis process may include representatives from the U.S. Marshals Service (for courthouses) and specialized security contractors to conduct more technical studies. GSA representatives and members of the Building Security Committee (BSC) are also included in the process.

Since such important and influential security assessments are made before design begins, without reference to any information about the project, Project Teams should revisit such assessments in this phase and plan to update them in Phase 2: Multidisciplinary Assessment.

In doing so, Project Teams should remember that GSA reserves the right to not implement a recommended mandatory measure as per the GSA/DHS Memorandum of Agreement, June 2006. Such a decision would be made only after consultation with DHS and only after written notification to DHS of the final decision. The final authority in this case rests with the appropriate GSA Assistant Regional Administrator (ARA) for the Public Buildings Service. Ideally, and far more often, DHS and GSA can reach consensus regarding the appropriate countermeasure as part of an effective design process.

GSA has created a number of tools to help Project Teams navigate the tradeoffs inherent in site security design projects. The GSA Security Charrette is a tool created to support the multidisciplinary approach envisioned in the ISC criteria. Recommended for initial use during the Feasibility Study, it can also culminate the Multidisciplinary Assessment phase ISC resources, and computer modeling tools are also available to support the process. The GSA Project Manager should become familiar with these tools and endorse their use by the Project Team. Please check GSA for the most up to date resources.

Communication and Information Sharing

A collaborative process is fundamental to good decision-making. Security experts, designers, and other stakeholders cannot provide meaningful input without comprehensive information sharing. Due to the sensitive nature of security assessments, this may not always happen. While it may be inappropriate to share some sensitive security related data with all parties, this should never impede true collaboration. Information that is designated "Law Enforcement Sensitive," for example, would be available only to those with the proper clearances. But on most federal projects, the information sufficient to weigh various alternatives would be designated "For Official Use Only (FOUO)." This information should be available to all of those involved in project decisions, including tenant agencies, consultants, and local officials.

The responsibility to share information with outside stakeholders increases where the envisioned countermeasures would have significant impacts on the surrounding neighborhood. For example, it is crucial to include outside stakeholders in discussions about setback distances, road closures, site amenities, and perimeter security. In these cases, sensitive building engineering studies or information about specific threats may be withheld, but the stakeholders must have enough information to understand the vulnerability that the team is addressing and the recommended countermeasures.

Team Assembly and Responsibilities

Selecting the right team members and consultants based on a project's scope of work and particular characteristics is key to a successful project. This requires some homework. Although the design community has focused attention on security for several years, there remains a relatively limited number of completed projects that illustrate best practices. So project leaders must be selective to ensure that the chosen consultants possess the right expertise.

Each team member brings a focused area of expertise to the project and accepts the corresponding responsibilities. Beyond the technical skills that each party contributes to the process, however, it is their participation in the rigorous, deliberative, design process with each other that yields the greatest value.

In order to deliver successful, holistic projects, each team member should share a sense of responsibility to meet each and every goal for the project. For example, blast experts should seek to provide a flexible range of alternatives that can support various site design concepts and daily use of the site. Designers should develop schemes that support a long-term vision for the site, beyond their immediate project. And local stakeholders who are responsible for neighborhood development should accept the need to reduce risk at the federal facility so that they can offer supportive solutions.

In light of this, it is important to remember that the Guide's recommended security design process might be a new experience for most team members. Designers and local stakeholders are likely to have limited experience with federal security decision making, while experienced security professionals may have limited experience making these decisions as part of a collaborative design process. For the Project Team leader, it is important to understand this and to lay out clear roles and responsibilities.

Phase 2. Multidisciplinary Assessment involves the Project Team using the zone approach to assess existing conditions on-site, including security vulnerabilities, context, and design opportunities.

- Analyze security vulnerabilities, site context, and opportunities throughout the entire site, using the zone approach to ensure a comprehensive view

- Assess security needs while heeding design opportunities, assess design needs while keeping in mind security opportunities; this is the foundation of the Multidisciplinary Assessment

Collaborative, Comprehensive Approach

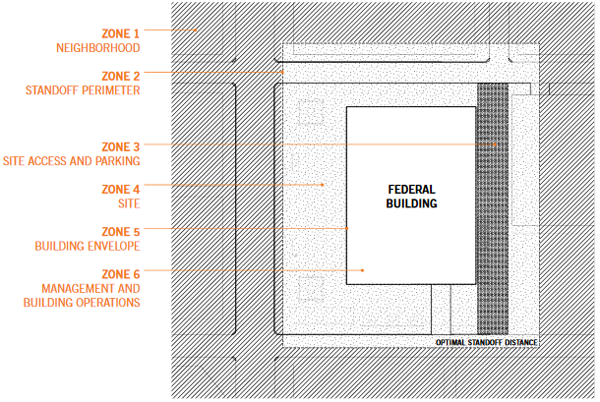

The zone approach provides common framework to assess existing conditions, including security vulnerabilities, site context, and opportunities. Project Teams consider each site in terms of six different zones (see Effective Site Security Design), each of which plays a particular role in overall security design. Solutions that consider the importance of each zone can meet the required level of protection creatively and comprehensively. Team members should keep in mind that a successful site security solution never exists solely in one zone and must function across all zones.

Site Security Zones

Project Teams must be vigilant to ensure that the information they use is complete and current. The benefits of previous assessments, whether of risk, facility condition, or other project aspects, should not be lost, but should be examined in the context of their purpose and date. All information should be assessed for current relevance as the project moves forward.

Whatever a project's size, the Project Team must begin by looking at the many aspects that directly and indirectly impact the overall design of site security. An example is shown below under APPLICATION, in which the site's existing conditions are analyzed and documented graphically on a site plan. This information is shared among the team members.

The activities in this phase include:

- site visits

- preparation and review of risk assessment

- review of existing GSA studies and documents

- collection of information from other sources

- meeting with stakeholders to understand the broader opportunities and requirements for the project.

(See the Site Security Design Guide for a checklist to guide this assessment process and a list of team roles and responsibilities.)

Risk Assessment

A DHS physical security specialist performs the risk assessment and analyzes threats (actual or perceived), vulnerability of sites and buildings, consequences, and probability of occurrence. This risk assessment considers Design Basis Tactics and Levels of Protection in making recommendations for Design Criteria. Other stakeholders provide additional considerations and contribute to the definition of protective measures. The activities and the products of this process guide all subsequent site security design.

On some projects, especially smaller ones or modernization projects, a completed risk assessment may already be available; Project Teams should ensure that this assessment is current. For other projects, a new risk assessment is prepared or a completed risk assessment is updated. In every case, security experts in conjunction with the larger Project Team examine the risk assessment within the broader project context. In every case, the analysis of security issues must heed the latest ISC criteria.

There are three key outcomes of every DHS risk assessment:

Design Basis Tactics identify the specific acts and methods that the building and site's countermeasures must protect against and form the basis for the site security design.

Level of Protection defines the performance that each affected building system requires. These performance levels are defined as Minimum, Low, Medium, or High and pertain to all affected systems, including glass, structure, and other components.

Design Criteria define the design direction that emerges, based on inputs from the risk assessment, consideration of the Design Basis Tactics, and the required Level of Protection.

Risk assessments also include two types of recommendations for protective measures:

- Optional Countermeasures. Actions that the risk assessment designates as "optional" are those addressing low or moderate risks where the ISC does not establish minimum performance requirements.

- Mandatory Countermeasures. Where the risk assessment identifies high-risk conditions that must be addressed, it defines "mandatory" countermeasures.

Design Assessment

Just as the security-focused aspects of the Multidisciplinary Assessment weigh the role of design, Project Teams must keep security functionality in mind as they assess the site's everyday use and the facility's relationship to its neighborhood.

By the end of Multidisciplinary Assessment, all Project Team members have an understanding of both the security and design opportunities of the site, and these are inherently interwoven. The products of this phase, which carry forward into subsequent phases, include the following:

- Risk Assessment:

- Design Basis Tactics

- Level of Protection

- Design Criteria

- Operational and Mandatory Countermeasures

- Preliminary Budget, Including Security Line Items

- Project Schedule

- Analysis of Neighborhood Opportunities and Constraints

- Site Analysis Summarizing Opportunities and Constraints:

- Utilities Plan

- Transportation and Circulation Plans

- Existing Topography, Vegetation, and Boundaries

- Analysis of Existing Building and Structures

- Program of Requirements for New Construction

The Project Team uses photos of existing conditions and an annotated site plan to document their initial site analysis.

Phase 3. Site Concept Investigation involves the Project Team developing, studying, and refining multiple alternative concepts for the entire site, in response to their findings from the Multidisciplinary Assessment. For large projects, the team may hold a peer review at this stage to help evaluate the alternatives.

- Develop multiple concepts that comprehensively address site-wide conditions, opportunities, and constraints identified in the Multidisciplinary Assessment phase

- Collaborate with project stakeholders and peers to examine these concepts, their ability to mitigate risk, and their impact on context

The design process is an iterative cycle that posits and tests multiple concepts in order to develop the best approach. It must be dynamic and interactive to be successful. During the Site Concept Investigation, the team develops, studies, and refines multiple concepts that explore a variety of options for the site design in response to the Multidisciplinary Assessment.

Project Team members discuss proposed concepts, their impacts, and their costs with GSA representatives, the Building Security Committee (BSC), security experts, other stakeholders, and peer reviewers. As these strategies are evaluated, Project Team members refine the best pieces and parts into new concepts. Project Team members may reevaluate their approach to security a number of times. In doing so, the team develops the most efficient and cost-effective approach to meet the needs of the project. Though the concepts become more refined and specific, they remain dedicated to the original site design strategy.

During this stage, fundamental strategies begin to take shape. For example, insufficient standoff distances may require significantly more hardening at a facility than would be required at a comparable facility where more standoff is available. It is important that Project Teams discuss such matters and options with the blast and security consultants before and during concept development. Spending time and money at this stage can save millions later in the project.

The Project Team must continue to look at the site overall, to ensure that the final design supports comprehensive, long-term site goals. Even when the project consists of only a specific area within the site (e.g., a high-priority perimeter), the Project Team must continue to address all aspects of the site. The Project Team will focus on the specific project area only in the last phases of the site security design process, when designers prepare final design and construction documents.

Once the important elements and issues are captured, the design team moves into the next phase of design, incorporating the information gathered from the concept investigations into a single concept for the site.

Phase 4. Site Concept Selection (Conceptual Strategy Plan) entails the Project Team forming a single alternative for the entire site, which comprises the best elements from the Site Concept Investigation. The team may hold a peer review in order to help select the site concept.

- Combine best results from site concept investigations into a "hybrid" concept (a Conceptual Strategy Plan)

- Reach consensus on basic strategies for security countermeasures and site improvements

- Begin consideration of budget and phasing to bring the design into built form

This phase should proceed seamlessly from the previous phase. Here, the design team develops a single alternative for the entire site, which comprises the best elements from the Site Concept Investigation.

The selected Site Concept should be a hybrid, balanced solution that incorporates and refines the most appropriate strategies and design elements from the many site concept studies. It should consider the entire site to ensure that solutions contribute to its overall improvement. In subsequent stages the Project Team will focus only on the specific project areas defined by the scope.

On smaller projects, the preferred concept can be chosen through informal peer reviews with GSA Regional experts and informed discussions among Project Team members. On larger projects, it is helpful to hold a formal peer review with design peers selected through GSA's Design Excellence program. They can provide an informed critique and foster discussion of costs and benefits.

Remember that risk can be mitigated and managed, but it can never be eliminated. Since it is not always possible to reduce risk through physical solutions alone, a successful Site Concept may depend on operational strategies, as well. These strategies should be considered an integral part of the risk management strategy and should also be agreed upon at this stage.

Phase 5. Design Studies for Project Areas involve the Project Team performing more detailed design work on key elements of the Site Concept, whether or not the entire Site Concept is implemented in a single project. The Design Studies begin the detailed design work that produces the final design of the immediate project.

- Perform a series of studies exploring different ways to achieve the goals of the Conceptual Strategy Plan

- Consider team expert input regarding the detailed approach for key areas

- Revisit budget and schedule goals and long-term maintenance and operations

These activities may involve the more complex or high priority areas of the overall site. Also, in cases where the entire site concept will not be implemented in a single project, these Design Studies may begin the detailed design work that the team will carry through to final design as part of the immediate project.

Using perspective sketches and renderings, the Design Studies further explore the ideas generated by the Conceptual Strategy Plan. The designers must test the Conceptual Strategy Plan against real site constraints and unseen obstacles, such as utility lines or underground vaults, which prevent barriers from attaining the structural foundations necessary to act as effective deterrents. Project Team members may contact additional consultants, such as structural engineers, to confirm site survey information and test assumptions.

The team reviews the Design Studies together and concentrates on important design details, with the larger site goals in mind. For example, in the Site Concept there may be a proposed perimeter wall along a portion of the site. During this stage, the security experts may comment on the likely performance of the proposed wall's construction or anchoring. Urban designers or local officials may advise on how the wall's details would impact neighborhood design goals.

Project designers provide a range of input on these issues and more, including material choices and information about cost and constructability. Ideally, as part of the discussion, security experts suggest alternatives that meet their performance requirements, while responding to the urban designers' concerns, and vice versa.

Larger strategy decisions are made during concept development in Phases 3 and 4, but this detailed design study phase is necessary to integrate countermeasures into the particular fabric of the site and its surroundings.

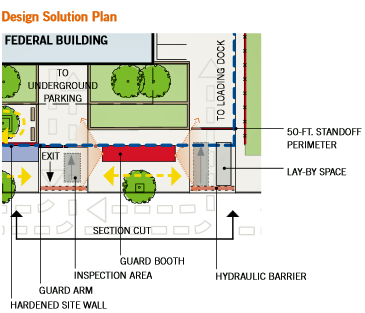

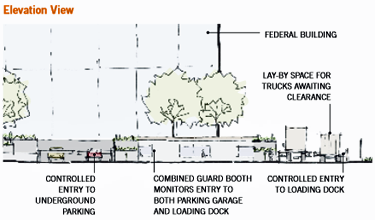

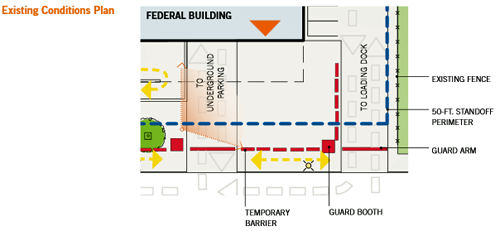

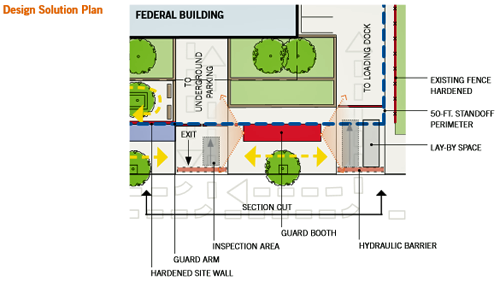

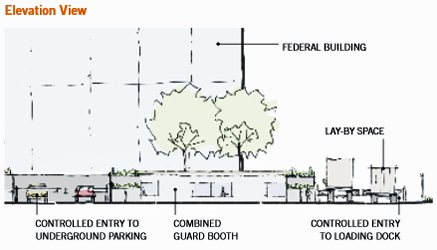

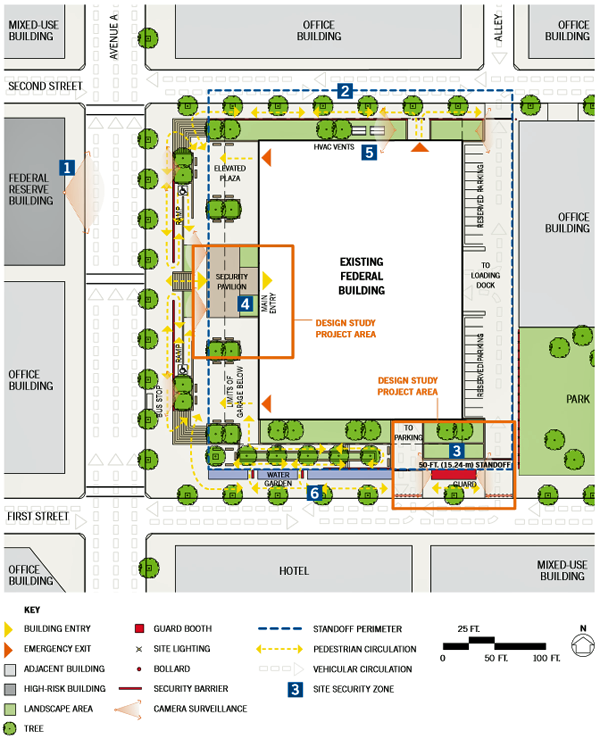

The Design Solution Plan and Elevation View of a conceptual solution in Zone 3 that combines three guard booths into one, which will save on operational and staffing costs, while centralizing security oversight. The placement of the guard booth also supports clear views of all vehicles entering the loading dock, as well as the underground parking entrance.

Phase 6. Final Concept Development entails the Project Team developing a detailed Final Concept for the project that will proceed forward into construction. At this stage, as part of the Design Excellence process, the team makes its Final Concept presentation to the stakeholders. Note that if the entire Site Concept from Phase 4 will not be implemented as part of the immediate project, this Final Concept Development may concentrate on only the portions of the project that will move forward into planned construction.

- Complete Final Concept for planned project

- Develop implementation and phasing plan (if necessary)

The team chooses the products, materials, and methods of implementation for the entire project scope, beyond the special areas that might have received more detailed design study in the previous phase. The Final Concept Plan should be true to the overall Site Concept (Conceptual Strategy Plan) from Phase 4 and responsive to the input received during the detailed Project Area Design Studies in Phase 5.

If the project is to be implemented in phases, the timing must be finalized for the most efficient use of materials and labor. Similarly, if the project is a renovation of an existing building, the Project Team must analyze the logistics of working on and around an occupied building.

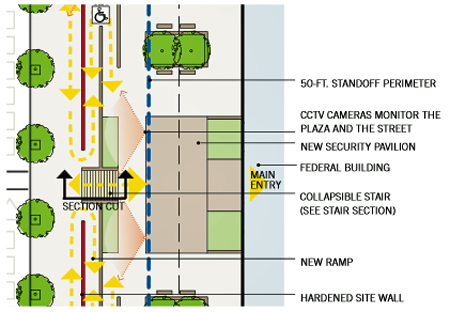

Key elements in this Final Concept Plan include surveillance cameras operated in conjunction with a neighboring federal building, a custom-designed guard booth, hardened site furniture, and a new security pavilion. The solution is integrated into the site and compatible with the building's architecture.

Phase 7. Final Design and Construction Documents involve the Project Team developing Site Concepts and Design Studies, culminating in the completion of construction documents. The Project Team conducts any testing of security measures at this time. Team members review final drawings and specifications to ensure that agreed-upon security elements are properly represented in the Final Design.

- Continue collaboration during this phase to ensure that the design and specifications stay consistent with concepts, materials, and budgets

- Coordinate site security elements with other aspects of the project

In this design-intensive stage, designers play the lead role. Other team members play an important role in reviewing drawings and specifications to ensure that agreed-upon elements are properly represented in the Final Design.

The development of design and construction documents may not require as much team involvement as other phases of the project. This may make coordination more challenging, as not every team member is needed at every meeting.

Phase 8. Project Completion and Operations entails the Project Team remaining involved, as needed, to respond to unforeseen conditions during construction and to alter the project design if necessary. As the project is completed and put into use, building management and security operations must continually evaluate the function of the physical countermeasures over time and remain committed to the operational security measures that help to form the complete solution.

- Collaborate to resolve last-minute concerns during construction

- Sustain commitment to security operations and maintenance after completion

Conclusion

A successful site security design process carries a project from initial conception to final completion, incorporating the elements and hallmarks as described in Effective Site Security, Site Security Design Case Study and the Site Security Design Guide thus far.

Site security design projects begin with the desire to transform existing conditions. Projects can successfully reduce risk and enhance the public realm when they are based upon meaningful security assessments, sensitivity to existing context and materials, and clear goals for desired site uses.

Application

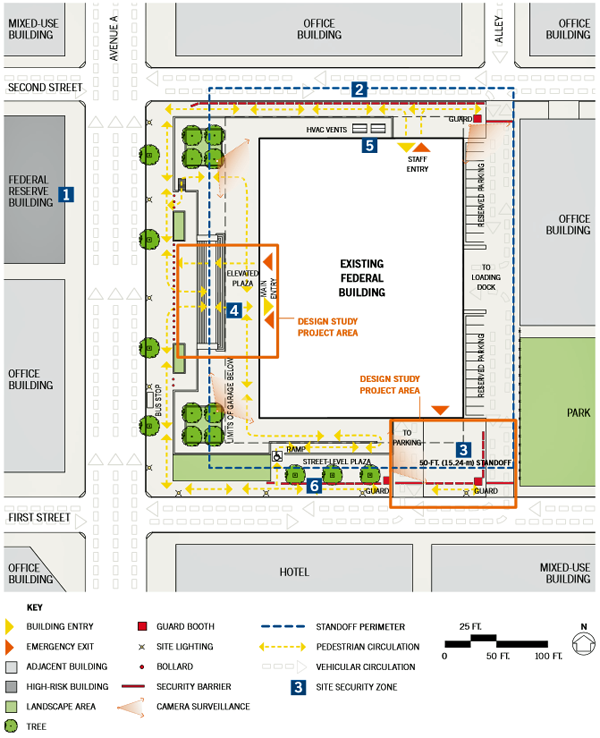

Test Case: Building Renovation / Urban Location: Single Building

This test case depicts a sole federal building occupying a block in an urban business district, located near the cultural core of a major metropolitan area. The high-rise building, built in the mid-20th century, sits on a plinth housing underground parking that is accessed from First Street and guarded by a staffed kiosk. The main building entry is not clearly delineated, thus creating confusion and crowding, as numerous visitors queue and wait in the plaza prior to security screening inside the building. HVAC vents/air intakes are located in an exposed location in an isolated corner of the elevated plaza. Temporary barriers, hastily installed throughout the site, have remained in place for years.

A loading dock and reserved surface parking area are located to the east side (rear) of the building, and staffed guard booths are positioned at both the First and Second Street entries. On the north side, an alley with one-way circulation aligns with access to the loading dock across Second Street.

The building received a medium ISC security rating, and the building's three tenant agencies have similar risk profiles. Although the Federal Reserve building across Avenue A is designated high risk, the surrounding buildings contain low-risk office space. The bus stop on Avenue A is the nearest public transportation stop to the building. (Additional test case studies may be found within the Site Security Design Guide.)

Existing Conditions / Site Context Plan

Test Case Existing Conditions / Site Context Plan

Test Case Assumptions

The Federal Reserve building on Avenue A desires enhanced security because of the vulnerability of its lobby area.

Temporary barriers have been placed at the curb line along the north side of the site, where there is insufficient standoff, and an alley allows direct approach into the loading dock.

The loading dock and the underground parking garage servicing the building both have access from First Street.

The main entry to the building is not clearly delineated, and crowding occurs at the elevated plaza, as visitors wait to pass through security screening.

There are exposed HVAC vents/air intakes accessible from the elevated plaza.

During a heightened security alert, temporary barriers were placed on the street-level plaza and have not been removed or replaced with permanent security fixtures.

Typical conditions seen in buildings of this type include a plinth that separates the main entry from the sidewalk, a main entry plaza, and curtain wall façade construction.

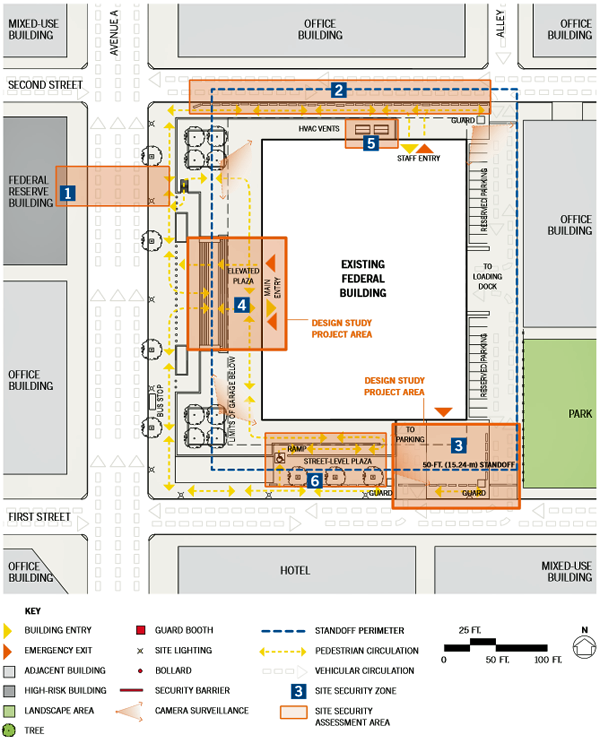

Site Security Assessment Plan

Test Case Site Security Assessment Plan

Security and Site Design Topics

A neighboring building with similar security concerns offers an opportunity for partnership and sharing of security resources.

Vector analysis of the northern site edge suggests that the northwest corner of the site warrants the most robust perimeter hardening. The middle of the block cannot easily be approached at high speed, and the alley that dead-ends into the loading dock presents only negligible risk of vehicular approach.

When parking is located under a building, that entry point is vulnerable.

Unmanaged queuing causes congestion and confusion that can make security monitoring difficult and public space less safe.

Exposed HVAC vents/air intakes are vulnerable to airborne chemical, biological, or radiological attack.

The temporary barriers at the street-level plaza are not rated to prohibit vehicular approach and have negative off-site impacts on the streetscape and adjacent local businesses.

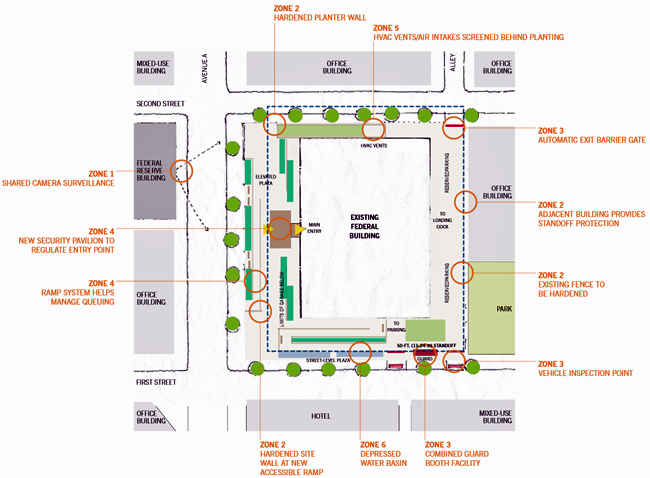

Conceptual Strategy Plan

Test Case Conceptual Strategy Plan

Project Area: Zone 3

Security Design Problem

Regulation of vehicular access to the site requires a combination of security elements to stop and screen cars and trucks prior to passing inside the perimeter. Ideally, access to on-site parking should be separated from service access because the screening process is different for each. A tenant with daily access requires a lower level of screening than a delivery truck. Multiple entry points require high operational overhead in terms of facilities and staffing. When parking is located underneath the building, that entry point is particularly vulnerable. An explosive-laden vehicle could penetrate the standoff perimeter and gain access to areas beneath the building.

Proposed Security Design Solution

To reduce operational costs and consolidate security oversight, a shared guard booth regulates access to both the underground parking garage and the loading dock. Guard arms designed as vehicular barriers control entry prior to security screening. Hydraulic barriers prevent a vehicle from backing into the street in the event that it needs to be detained. If possible, vehicles should be stopped outside the 50-foot standoff perimeter for inspection. Due to the constraints of this site and the space required for a truck to pull off the street completely to avoid stopping traffic, the guard arm at the loading dock is located slightly within the standoff perimeter. A lay-by space enables trucks that are waiting for security clearance to pull to the side, allowing other vehicles to pass.

Project Area: Zone 4

Security Design Problem

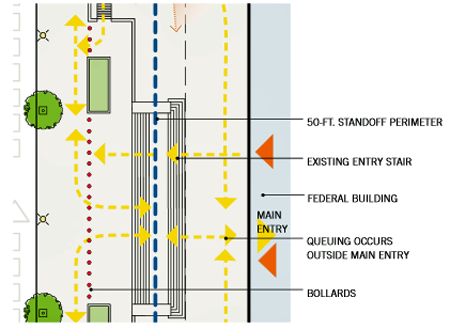

Existing buildings often have main building entries and lobbies that were not designed for current security processes and equipment and are difficult to reconfigure. A typical modernist building with a curtain wall façade may have multiple main doors and few visual cues to direct visitors to the appropriate entry for screening. This can cause confusion, especially if the building has a high degree of public use. Crowding may occur as visitors wait to be processed through the security checkpoint. If not properly controlled, queuing can create disorder and make security oversight more difficult.

Proposed Security Design Solution

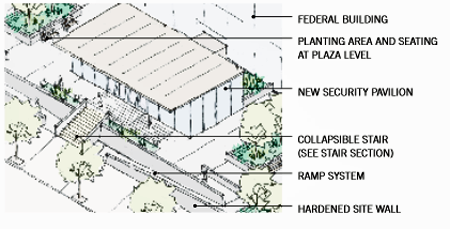

A security pavilion outside the main building provides the additional space required to accommodate the security equipment and guards needed to screen visitors prior to entry. The pavilion clearly delineates the "front door" to the building and provides cover for visitors waiting for entry. Due to the size of the pavilion, the elevated plaza is reconfigured. The main entry is rebuilt to incorporate a new collapsible stair and accessible ramps. The collapsible stair incorporates a compressible fill that supports pedestrian traffic, but will fail under the weight of a vehicle. A reinforced knee wall built into the stair prevents further approach. The ramps, which provide universal access, also offer additional area for queuing overflow. The walls alongside the ramps guide queues and offer room to sit and wait. The elevated plaza provides open space for casual seating and a large area for public programs or demonstrations.

Final Concept Plan

Test Case Final Concept Plan

Security and Site Design Solutions

Cameras mounted on the façade of the Federal Reserve building monitor activity in front of the existing federal building, while cameras placed at key locations on the elevated plaza monitor activity along Avenue A to create shared surveillance of the street.

Based on vector analysis, a hardened site wall provides protection from vehicles. The site wall varies in height according to risk; at midblock, where high-speed approach is less possible, the wall is seat height. Traffic into the loading dock is limited to entry from First Street, and an automatic security gate regulates egress onto Second Street.

A vehicle checkpoint with shared guard facilities provides the room and equipment to adequately screen vehicles before they enter the site.

A security pavilion at the plaza level creates space outside the existing federal building to screen visitors and manage queuing.

Planting areas, grates, and filters protect the HVAC vents/air intakes from unregulated access.

The temporary barriers are removed and replaced by security elements, such as site walls and a moat that is also a water garden at the street-level plaza. Multipurpose features minimize risk and improve the quality of public space.

In improving security at existing buildings, envision potential improvements in terms of the entire site, the community, and broader neighborhood development efforts. The introduction of a security pavilion provides occasion to revisit the usability of adjacent public spaces, while new security walls present an opportunity to improve the landscape or commission a public artwork. Such comprehensiveness enhances the safety and quality of the workplace, while ensuring that the federal government is a good neighbor.

Additional Resources

Publications

- GSA and its partner agencies have developed many tools and techniques to support better security for GSA buildings, as well as the expertise to apply these tools to GSA projects. The following tools are available through GSA to those involved with appropriate projects. The use of these tools requires the input of security consultants, including representatives from DHS's Federal Protective Service (FPS) and blast consultants.

- Facility Security Level Determinations for Federal Facilities. An Interagency Security Committee Standard. For Official Use Only

- Federal Facility Security Committee Standard. An Interagency Security Committee Document. For Official Use Only.

- Physical Security Criteria for Federal Facilities. An Interagency Security Committee Standard. For Office Use Only.

- The Design-Basis Threat (U). An Interagency Security Committee Report. For Official Use Only.

- The Site Security Design Guide by GSA. Washington, DC: June 2007

Computer Modeling of Hazards and Impacts

GSA and its consultants employ a variety of proprietary computer programs to assist in security assessments and countermeasure analysis. Two of the most prominent for GSA projects are WINGARD (WINdow Glazing Analysis Response & Design) and STANDGARD (STANDard GSA Assessment Reporter & Database), which determine potential hazards from explosions and assess vulnerability.