Introduction

Within This Page

Facilities operations and maintenance encompasses a broad spectrum of services, competencies, processes, and tools required to assure the built environment will perform the functions for which a facility was designed and constructed. Operations and maintenance typically includes the day-to-day activities necessary for the building/built structurei, its systems and equipment, and occupants/users to perform their intended function. Operations and maintenance are combined into the common term O&M because a facility cannot operate at peak efficiency without being maintained; therefore the two are discussed as one.

The Facilities O&M section offers guidance in the following areas:

- Real Property Inventory (RPI)—Provides an overview on the type of system needed to maintain an inventory of an organization's physical assets and manage those assets.

- Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS)—Contains descriptions of procedures and practices used to track the maintenance of an organization's assets and associated costs. hese projects are commonly repetitive, include preventive, planned/scheduled, and emergency activities, with projects under and established dollar threshold (i.e, $15,000).

- Computer Aided Facilities Management—originally referred to space planning technologies, however, is not used more generically to describe a variety of technologies addressing any or all aspects of Facilities Management. Examples include

CMMS, BIM, IWMS, and others.

- O&M Manuals—it is now widely recognized that O&M represents the greatest expense in owning and operating a facility over its life cycle. The accuracy, relevancy, and timeliness of well-developed, user-friendly O&M manuals cannot be overstated. Hence, it is becoming more common for detailed, facility-specific O&M manuals to be required as a part of the total commissioning process. These manuals describe the processes, methods, tools, components, and frequencies involved for requisite operations and management of physical assets.

- Janitorial/Cleaning—As the building is opened the keys are turned over to the janitorial, custodial or housekeeping staff for interior "cleaning" and maintenance. Using environmentally friendly cleaning products and incorporating safer methods to clean buildings provides for better property asset management and a healthier workplace. Grounds maintenance and proper cleaning of exterior surfaces are also important to an effective overall facility maintenance and cleaning program. Janitorial/Cleaning, as well as Landscaping, Snowplowing, etc. are considered to be General Maintenance Activities.

-

Historic Buildings Operations and Maintenance—this is a unique and complex issue: balancing keeping old equipment running while contemplating the impact of installing new more efficient equipment. Further, cleaning of delicate surfaces and artwork require the use of products that are less likely to damage these surfaces, while providing a healthy environment for the building's occupants. Maintaining strict temperature and humidity control to protect artwork and antiquities is an additional challenge for the O&M staff. Extensive research has been done by the Smithsonian Institution regarding the effect of temperature and humidity on artifacts and can be found in the following links:

Determining the Acceptable Ranges of Relative Humidity and Temperature in Museums and Galleries: Part 1 and Part 2

For more information go to The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, under the Documents & References section of the WBDG or to the Sustainable Historic Preservation.

- Project Delivery Methods—The process established to efficiently define, cost, procure, execute, and manage operations and maintenance projects is referred to as the project delivery method. As there are numerous and disparate operations and maintenance projects facing real property owners and their service providers, it is critical that they be accomplished in a timely and cost-effective manner. While traditional construction delivery methods such as design-bid-build have commonly been used, collaborative construction delivery methods such as Job Order Contracting have demonstrated to be capable of delivering over 90% of these types of projects on-time, on-budget, and to the satisfaction of all participants and oversight groups.

The scope of O&M includes the activities, processes, and workflows required to keep the entire built environment as contained in the organization's Real Property Inventory of facilities and their supporting infrastructure, including utility systems, parking lots, roads, drainage structures and grounds in a condition to be used to meet their intended function during their life cycle. These activities include both planned preventive and predictive maintenance and corrective (repair) maintenance. Preventive Maintenance (PM) consists of a series of time-based maintenance requirements that provide a basis for planning, scheduling, and executing scheduled (planned versus corrective) maintenance. PM includes adjusting, lubricating, cleaning, and replacing components. Time intensive PM, such as bearing/seal replacement, would typically be scheduled for regular (plant or "line") shutdown periods. Per the Federal Energy Management Program (FEMP), Predictive Maintenance attempts to detect the onset of a degradation mechanism with the goal of correcting the degradation prior to significant deterioration in the component or equipment. Corrective maintenance is a repair necessary to return the equipment to properly functioning condition or service and may be either planned or un-planned. Some equipment, at the end of its service life, may warrant overhaul. Per DOD, the definition of overhaul is the restoration of an item to a completely serviceable condition as prescribed by maintenance serviceability standards.

Requirements will vary from a single facility, to a campus, to groups of campuses. As the number, variety, and complexity of facilities increase, the organization performing the O&M should adapt in size and complexity to ensure that mission performance is sustained. In all cases O&M requires a knowledgeable, skilled, and well trained management and technical staff and a well planned maintenance program. The philosophy behind the development of a maintenance program is often predicated on the O&M organization's capabilities. The goals of a comprehensive maintenance program include the following:

- Reduce capital repairs

- Reduce unscheduled shutdowns and repairs

- Extend equipment life, thereby extending facility life.

- Realize life-cycle cost savings, and

- Provide safe, functional systems and facilities that meet the design intent.

Sustainability is an important aspect of the O&M process. A well run O&M program should conserve energy and water and be resource efficient, while meeting the comfort, health, and safety requirements of the building occupants. The impact of Energy Policy Act of 2005 (EPAct 2005), the Executive Order 13693 and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA 2007) must all be considered in the facilities O&M process. The Federal High Performance and Sustainable Buildings section provides key information needed by Federal personnel to meet high performance and sustainable building requirements.

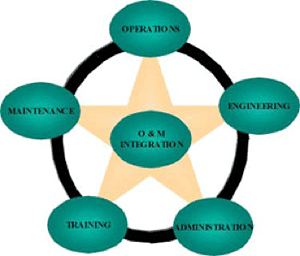

A critical component of an overall facilities O&M program is its proper management. Per FEMP, the management function should bind the distinct parts of the program into a cohesive entity. The overall program should contain five distinct functions: Operations, Maintenance, Engineering, Training, and Administration (OMETA). Beyond establishing and facilitating the OMETA links, O&M managers have the responsibility of interfacing with other department managers and making their case for ever shrinking budgets.

Related Issues

System-level O&M Manuals. Organizations that require a higher level of O&M information beyond the typical vendor equipment documents should ensure sufficient funds are set aside and appropriate scope/content/format requirements are identified during the planning stage. It is important to analyze and evaluate a facility from the system level, then develop procedures to attain the most efficient systems integration. System-level manuals include as-built information, based on the maintenance program philosophy. O&M procedures at the system level do not replace manufacturers' documentation for specific pieces of equipment, but rather supplement those publications and guide in their use. For example, system-level troubleshooting will fault-analyze to the component level, such as a pump, valve or motor, then reference specific manufacturer requirements to remove, repair, or replace the component. Documentation should typically meet or exceed client or commercial standards, such as ASHRAE Guidelines (e.g., Guideline 4-2008 (R 2013) Preparation of Operating and Maintenance Documentation for Building Systems) for format and content, and be tailored specifically to support the Owner's Maintenance Program (MP).

Historic Buildings Operations and Maintenance. This is a unique and complex issue: balancing keeping old equipment running while contemplating the impact of installing new more efficient equipment. Further, cleaning of delicate surfaces and artwork require the use of products that are less likely to damage these surfaces, while providing a healthy environment for the building's occupants. Maintaining strict temperature and humidity control to protect artwork and antiquities is an additional challenge for the O&M staff. Extensive research has been done by the Smithsonian Institution regarding the effect of temperature and humidity on artifacts and can be found in the following links:

-

Determining the Acceptable Ranges of Relative Humidity and Temperature in Museums and Galleries: Part 1 and Part 2

For more information go to The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties, under the Documents & References section of the WBDG or to the Sustainable Historic Preservation.

- Operations and Maintenance for Historic Structures

- Common Data Environment (CDE)— a shared built environment taxonomy spanning fully defined and consistently used terms and definitions described in plain language and data architectures such as COBie, MasterFormat, Uniformat, Omniclass, etc.

Construction Operations Building Information Exchange (COBie). Consideration to implement COBie should be identified during the planning stage, especially when BIM is required.

Federal Real Property Asset Management (Executive Order 13327–2004). Under this directive federal agencies are required to establish procedures to establish accountability and stewardship for all owned and maintained federal facilities. This includes reporting value, condition and sustainability as well as adopting principles of total cost of ownership and life-cycle costing.

Deferred Maintenance. The method of determining the value of an organization's deferred maintenance has been in discussion over the past decade. In 1995 the Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board (FASAB) established Accounting Standard Number 6 which defined and established the requirements for reporting of deferred maintenance. This led to the federal community to determine how to meet these requirements and in 1999 the Federal Facilities Council Standing Committee on Operations and Maintenance published Technical Report 141 – Deferred Maintenance for Federal Facilities. This report further defined maintenance as well as repairs. The FASAB is in the process of revisiting the issue of deferred maintenance and how it is defined and determined. Also, a recent GAO report questioned the differences that existed in defining and determining an agency's method of reporting deferred maintenance (see GAO-09-10 Report – Federal Real Property: Government's Fiscal Exposure from Repair and Maintenance Backlogs Is Unclear – October 2008). Also, the FFC has funded research for predicting organizational outcomes anticipated from investments in facilities maintenance and repair. All these efforts will have an impact as to how a federal agency will account for and track maintenance and repair costs and the backlog of deferred maintenance.

Sustainability. Recent directives have established goals for reduction of energy and water usage and to improve the sustainability of both new buildings as well as existing buildings (see Executive Order 13693, "Planning for Federal Sustainability in the Next Decade" and the Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA 2007)). This will impact how facilities are operating and how they are maintained. The Federal High Performance and Sustainable Buildings section provides key information needed by Federal personnel to meet high performance and sustainable building requirements.

Emerging Issues

Teardowns. Demolishing older or historic buildings and replacing them with new structures that may not be as durable, sustainable or secure is a problem found in many communities in both the government and private sector. Currently there is no single tool available to solve the Teardown problem but rather a combination of strategies works best. One tool available online is "Teardown Tools on the Web," created as part of the National Trust for Historic Preservation Teardowns Initiative. This tool is intended as an easy-to-share, user-friendly, one-stop-shop highlighting approximately 30 tools and more than 300 examples of best practices in use in the United States.

Additional Resources

A. Planning and Design Phase

O&M activities start with the planning and design of a facility and continue through its life cycle. During the planning and design phases, O&M personnel should be involved and should identify maintenance requirements for inclusion in the design, such as equipment access, built-in condition monitoring, sensor connections, and other O&M requirements that will aid them when the built facility is turned over to the owner/user organization. The O&M team should be represented on the project development team so they know ahead of time the types of controls, equipment and systems they will have to maintain once the facility is turned over to them. For more on this subject, see "F. Coordinating Staff Capabilities and Training with Equipment and System Sophistication Levels." Consideration should be given for professionally developed system-level O&M Manual(s), rather than the typical vendor-supplied equipment manuals. The Construction Operations Building Information Exchange (COBie) initiative should also be a consideration. For larger complexes, O&M staff should consider system-wide integration and compatibility of proposed products with existing systems, including tools, equipment and cleaning supplies. This is where the full system commissioning process starts. WBDG—Construction Operations Building Information Exchange (COBie)

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance Best Practices Guide by the Department of Energy (DOE)—Chapter 3: O&M Management, Chapter 9: Pump Design / Selection

- EPA I-BEAM—The Indoor Air Quality Building Education and Assessment Model (I-BEAM) is a guidance tool designed for use by building professionals and others interested in indoor air quality in commercial buildings.

- Chapter - Ductwork cleaning/standards

- Chapter - Exhaust System Design

- PBS-P100 Facilities Standards for the Public Buildings Service by the General Services Administration (GSA)—Appendix A.3 New Construction and Modernization and Appendix A.4 Alteration Projects

B. Construction Phase

To support efficient Operation and Maintenance (O&M), it is important that facility O&M documentation (1) be required by the owner and (2) be accurate, and (3) be available in a timely fashion. System-level and manufacturer manuals of as-installed systems and equipment, including as-built drawings, should be available for review by the owner over the course of the Construction Phase. However, it is not uncommon for this documentation to be delivered at fiscal closeout, long after the owner has moved into the building. To efficiently operate a facility at turnover, O&M information must be available prior to fiscal completion, owner occupancy, and especially before operator/maintainer training. If this currently is not the case, owners may need to revise their procurement specifications to mandate the requirement. Although obtaining O&M documentation may be overseen by the owner's representative or building commissioning agent, the effort should be coordinated with/overseen by the owner's construction manager to ensure it is being accomplished.

In addition, typically part of the construction contract, warranties/activation dates and spare parts information should be organized and tracked.

- WBDG–Construction Operations Building Information Exchange (COBie)

- WBDG–Building Commissioning

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance Best Practices Guide by the Department of Energy (DOE)—Chapter 7: Commissioning Existing Buildings

- ENERGY STAR® Building Upgrade Manual—Chapter 5: Retrocommissioning

- Example Retro-Commissioning Scope of Work by the Department of Energy (DOE).

- Society for Machinery Failure Prevention Technology

- TM 5-697 Commissioning of Mechanical Systems for Command, Control, Communications, Computer, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) Facilities by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

- Building Commissioning Guide by the General Services Administration (GSA).

- ASHRAE Guideline 0-2013

C. O&M Approach

The O&M organization is typically responsible for operating and for maintaining the built environment. To accomplish this, the O&M organization must operate the systems and equipment responsibly and maintain them properly. The utility systems may be simple supply lines/systems or may be complete production and supply systems. The maintenance work may include planned preventive/predictive/ and maintenance, corrective (repair) maintenance, trouble calls, (e.g., a room is too cold), replacement of obsolete items, predictive testing & inspection, overhaul, and grounds care. O&M organizations may utilize a Reliability-Centered Maintenance (RCM) program that includes "the optimum mix of reactive, time- or interval-based, condition-based, and proactive maintenance (predictive/planned) practices These primary maintenance strategies, rather than being applied independently, are integrated to take advantage of their respective strengths in order to maximize facility/equipment reliability, while minimizing life-cycle costs." Particularly for Heating, Ventilating, and Air Conditioning (HVAC) systems, retro-commissioning is an option to improve operating efficiencies. The O&M organization is also normally responsible for maintaining records on deferred maintenance (DM), i.e. maintenance work that has not been accomplished because of some reason—typically lack of funds.

- Instruction 32-1051 Roof Systems Management by the Air Force (USAF).

- UFC 3-601-02 O&M: Inspection, Testing, and Maintenance of Fire Protection Systems by the Department of Defense (DOD).

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance Best Practices Guide by the Department of Energy (DOE)—Chapter 5: Types of Maintenance Programs, Chapter 9: O&M Ideas for Major Equipment Types

- Federal Acquisition Service—Elevator inspection/repair by the General Services Administration (GSA).

- ENERGY STAR® Building Upgrade Manual—Chapter 6 Lighting, Chapter 8 Air Distribution Systems

- EPA I-BEAM—The Indoor Air Quality Building Education and Assessment Model (I-BEAM) is a guidance tool designed for use by building professionals and others interested in indoor air quality in commercial buildings.

- Chapter - Cooling Towers

- Society for Machinery Failure Prevention Technology

- TM 5-692-1 Maintenance of Mechanical and Electrical Equipment at Command, Control Communications, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) Facilities by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

- TM 5-692-2 Maintenance of Mechanical and Electrical Equipment at Command, Control, Communications, Computers, Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (C4ISR) Facilities by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

- UFC 3-110-04 Roofing Maintenance and Repair by the Department of Defense (DOD).

- LEED for Existing Buildings: Operations and Maintenance by the U.S. Green Building Council (USGBC).

- Deferred Maintenance Reporting for Federal Facilities: Meeting the Requirements of Federal Accounting Standards Advisory Board Standard Number 6, as Amended

D. Life-Cycle O&M

According to the International Facilities Management Association (IFMA), the operating life-cycle costs of a facility typically are comprised of 2% for design and construction, 6% for O&M and 92% for occupants' salaries. O&M of the elements included in buildings, structures and supporting facilities is complex and requires a knowledgeable, well-organized management team and a skilled, well-trained work force whether the functions are performed in-house or contracted. The objective of the O&M organization should be to operate, maintain, and improve the facilities to provide reliable, safe, healthful, energy efficient, and effective performance of the facilities to meet their designated purpose throughout their life cycle. To accomplish these objectives, O&M management must manage, direct, and evaluate day-to-day O&M activities and budget funds to support the organization's requirements. For federal agencies Full Life Cycle Costing is a requirement of the 2004 Executive Order 13327—Federal Real Property Asset Management.

- WBDG—Construction Operations Building Information Exchange (COBie)

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance Best Practices Guide by the Department of Energy (DOE)—Chapter 3: O&M Management, Chapter 5: Types of Maintenance Programs, Chapter 8: Metering for Operations and Maintenance

- ENERGY STAR® Operation and Maintenance (O&M) Reports

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance

- Society for Machinery Failure Prevention Technology

- The Pennsylvania Green Building Operations and Maintenance Manual

E. Computerized Maintenance Management Systems

O&M organizations may utilize Computerized Maintenance Management Systems (CMMS) to manage their day-to-day operations and to track the status of maintenance work and monitor the associated costs of that work. These systems are vital tools to not only manage the day-to-day activities, but also to provide valuable information for preparing facilities key performance indicators (KPIs)/metrics to use in evaluating the effectiveness of the current operations and to support organizational and personnel decisions. These systems are starting to be integrated more and more with Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Building Information Modeling (BIM) technologies and COBie to increase/improve a facility's operational functionality.

- FEMP Operations and Maintenance Best Practices Guide by the Department of Energy (DOE)—Chapter 4: Computerized Maintenance Management System

F. Coordinating Staff Capabilities and Training with Equipment and System Sophistication Levels

O&M organizations must address the skill level of their staff in light of the O&M systems and components within their facilities. This extends beyond the in-house staff to any contracted services as well. If the skills required to support installed systems and equipment are scarce, either training must be provided or less sophisticated equipment systems utilized to provide an economical working arrangement.

With the natural industry progression of incorporating technology advances into renovations, major capital repairs and new building construction, high-tech building systems are being placed into service that current O&M staff are not familiar enough with to properly correct problems when they arise, or to keep operating efficiently. An example of this is building automation systems (BAS). Often untrained personnel will override programmed settings with manual settings that address specific hot/cold call issues, but over time these cumulative overrides result in un-balanced system-wide operations.

Regardless of their equipment sophistication levels, every organization should develop training programs and track staff qualifications to ensure they are adequate for existing and planned building systems. This will allow organizations to make improvements to training as needed on an ongoing basis. A recurring training program should consider both the type of skills required and the available labor pool skills in the geographic area. Topics for consideration include the following:

- Safety/OSHA regulations and guidelines

- Equipment operational start-up and shutdown procedures

- Normal operating parameters

- Emergency procedures

- Equipment preventative maintenance (PM) plans

- The use of proper tools and materials, to include personal protective equipment (PPE)

Training programs should be reviewed at least annually and whenever changes are planned for equipment or new facilities. In addition to regular assessments of the O&M staff's technical abilities concerning existing equipment, the staff should always be included throughout new project development efforts by design teams. The O&M staff can provide valuable inputs to match the workforce's abilities and training plans with any new equipment. The O&M staff is usually one of the best sources for input on how an existing facility is performing, and they can provide insight into how new equipment will be incorporated into facility maintenance programs. The staff may not always understand the underlying cause of a building problem, but they can identify areas that receive repeated attention in efforts to correct a long-standing condition. O&M staff inputs can guide designers to address these areas in renovation and equipment upgrade projects. A simpler equipment solution should be pursued if the needs of specific equipment cannot be addressed long-term with available labor resources due to technological levels.

Qualified personnel are needed to operate and maintain facilities at peak efficiencies, and to protect significant investments in equipment and systems. Besides posing a potential physical hazard to themselves and others, untrained employees can unknowingly damage equipment and cause unnecessary downtime. Inefficient and improper O&M can also void warranties and reduce expected useful life (EUL) of equipment.

Certifications and proper training of O&M service providers protect the organization, employees, and visitors. Training sources include manufacturers, professional organizations, trade associations, universities and technical schools, commercial education/training courses, and in-house training and on the job training (OJT) options. Training programs should provide an appropriate mix of these sources to the workforce to ensure materials addressed are up to date and applicable to the organization's facilities.

G. Non O&M Work

Most O&M organizations typically also perform work that is beyond the definition of O&M, but is so often required and performed by them, that the work often becomes a part of their baseline. This work is facilities-related work that is new in nature, and as such, should not be funded with O&M funds but funded by the requesting organization. Examples can include minor facilities work—such as installing an outlet to support a new copier machine, providing a compressed air outlet to a new test bench, day porter services for special event set-ups and moves—or a complete room rehab and/or new, small construction projects. Methods available to document the built environment's condition and its maintenance/repair needs include the periodic Facility Condition Assessment (FCA).

H. Janitorial/Green Cleaning

- Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

- FedCenter Acquisition - Buy Green

- Green Cleaning—Seattle Public Utilities

- Green Seal

- Training for Building Cleaning and Maintenance Professionals—Cleaning Management Institute

- USDA BioPreferred Program

- What to Put in a Green Cleaning RFP, Stephen Ashkin and Jennifer Corbett-Shramo, Building Operating Management

Training Courses

- WBDG04 Optimizing Operations and Maintenance (O&M)

- FEMP18 Best Practices for Comprehensive Water Management for Federal Facilities

- FEMP45 2016 Guiding Principles Introduction and Guiding Principle I, Employ Integrated Design Principles

- FEMPFTS27 O&M Best Practices for Small-Scale PV Systems

- FEMPFTS23 Re-Thinking Operations & Maintenance for High Performance Buildings

Metrics / Key Performance Indicators

- Custodial Costs per square foot

- Grounds Keeping Costs per square foot

- Energy Costs per square foot

- Energy Usage

- Facility Operating Current Replacement Value (CRV) Index (SAM Performance Indicator: APPA 2003)

- Facility Operating Gross Square Foot (GSF) Index (SAM Performance Indicator: APPA 2003)

- Metrics/Cost Models

- Utility Costs per square foot

- Waste Removal Costs per square foot

Definitions

-

Emergency Maintenance — Unscheduled work that requires immediate action to restore services, to remove problems that could interrupt activities, or to protect life and property. Unscheduled/Unplanned Maintenance Reactive and non-emergency corrective work activities that occur in the current budget cycle or annual program. Activities may range from unplanned maintenance of a nuisance nature requiring low levels of skill for correction, to non-emergency tasks involving a moderate to major repair or correction requiring skilled labor.

-

Emergency Repairs — Requests for system or equipment repairs that are unscheduled and unanticipated. Service calls generally are received when a system or component has failed and/or perceived to be working improperly. If the problem has created a hazard or involves an essential service, an emergency response may be necessary. Conversely, if the problem is not critical, a routine response is adequate.

-

Energy Usage — This performance indicator is expressed as a ratio of British Thermal Units (BTUs) for each Gross Square Foot (GSF) of facility, group of facilities, site, or portfolio. This indicator represents a universal energy consumption metric that is commonly considered a worldwide standard. This energy usage metric can be tracked over a given period of time to measure changes and variances of energy usage. Major factors that affect BTU per gross square foot are outside ambient temperature, building load changes, and equipment efficiencies. The amount of energy it takes for heating, cooling, lighting, and equipment operation per gross square foot. The indicator is traditionally represented as total energy consumed annually or monthly. All fuels and electricity are converted to their respective heat, or BTU content, for the purpose of totaling all energy consumed. Energy Usage = British Thermal Units BTUs /Gross Area GSF.

-

Facility Operating Current Replacement Value (CRV) Index — This indicator represents the level of funding provided for the stewardship responsibility of an organization's capital assets. The indicator is expressed as a ratio of annual facility maintenance operating expenditure to current replacement value (CRV). Annual facility maintenance operating expenditures includes all expenditures to provide service and routine maintenance related to facilities and grounds. It also includes expenditures for major maintenance funded by the annual facilities' maintenance operating budget. This category does not include expenditures for major maintenance and/or capital renewal funded by other accounts, nor does it include expenditures for utilities and support services such as mail, telecommunications, public safety, security, motor pool, parking, environmental health and safety, central receiving, etc. Facility Operating CRV Index = Annual Facility Maintenance Operating Expenditures ($) / Current Replacement Value ($).

-

Facility Operating Gross Square Foot (GSF) Index — This indicator represents the level of funding provided for the stewardship responsibility of an organization's capital assets. The indicator is expressed as a ratio of annual facility maintenance operating expenditure to the institution's gross area. Annual facility maintenance operating expenditures includes all expenditures to provide service and routine maintenance related to facilities and grounds. It also includes expenditures for major maintenance funded by the annual facilities' maintenance operating budget. This category does not include expenditures for major maintenance and/or capital renewal funded by other institutional accounts, nor does it include expenditures for utilities and support services such as mail, telecommunications, public safety, security, motor pool, parking, environmental health and safety, central receiving, etc. Facility Operating GSF Index = Annual Facility Maintenance Operating Expenditures ($) / Gross Area (GSF).

-

Normal/Routine Maintenance and Minor Repairs — Cyclical, planned work activities funded through the annual budget cycle, done to continue or achieve either the originally anticipated life of a fixed asset (i.e., buildings and fixed equipment), or an established suitable level of performance. Normal/routine maintenance is performed on capital assets such as buildings and fixed equipment to help them reach their originally anticipated life. Deficiency items are low in cost to correct and are normally accomplished as part of the annual operation and maintenance (O&M) funds. Normal/routine maintenance excludes activities that expand the capacity of an asset, or otherwise upgrade the asset to serve needs greater than, or different from those originally intended.

-

Operations — All activities associated with the routine, day to day use, support, and maintenance of a building or physical asset; inclusive of administration, management fees, normal/routine maintenance, custodial services and cleaning, fire protection services, pest control, snow removal, grounds care, landscaping, environmental operations and record keeping, trash-recycle removal, security services, service contracts, utility charges (electric, gas/oil, water), insurance (fire, liability, operating equipment) and taxes. It does not include capital improvements. This category may include expenditures for service contracts and other third-party costs. Operational activities may involve some routine maintenance and minor repair work that are incidental to operations but they do not include any significant amount of maintenance or repair work that would be included as a separate budget item.

-

Planned or Programmed Maintenance — Includes those maintenance tasks whose cycle exceeds one year. Examples of planned or programmed maintenance are painting, flood coating of roofs, overlays and seal coating of roads and parking lots, pigging of constricted utility lines, and similar functions.

-

Predictive Maintenance/Testing/Inspection — Routine maintenance, testing, or inspection performed to anticipate failure using specific methods and equipment, such as vibration analysis, thermographs, x-ray, or acoustic systems to aid in determining future maintenance needs. For example, tests to locate thinning piping, fractures, or excessive vibration that are indicative of maintenance requirements.

-

Preventive Maintenance — A planned, controlled program of periodic inspection, adjustment, cleaning, lubrication, and/or selective parts replacement of components, and minor repair, as well as performance testing and analysis intended to maximize the reliability, performance, and lifecycle of building systems, equipment, etc. Preventive maintenance consists of many check point activities on items, that if disabled, may interfere with an essential installation operation, endanger life or property, or involve high cost or long lead time for replacement.

-

Programmed Major Maintenance — Includes those maintenance tasks whose cycle exceeds one year. Examples of programmed major maintenance are painting, roof maintenance, (flood coating), road and parking lot maintenance (overlays and seal coating), utility system maintenance (pigging of constricted lines), and similar functions.

-

Repair(s) — Work that is performed to return equipment to service after a failure, or to make its operation more efficient. The restoration of a facility or component thereof to such condition that it may be effectively utilized for its designated purposes by overhaul, reprocessing, or replacement of constituent parts or materials that have deteriorated by action of the elements or usage and have not been corrected through maintenance.

-

Routine Repairs — Actions taken to restore a system or piece of equipment to its original capacity, efficiency, or capability. Routine repairs are not intended to increase significantly the capacity of the item involved. For example, the replacement of a failed boiler with a new unit of similar capacity would be a routine repair project. However, if the capacity of the new unit were to double the capacity of the original unit, the cost of the extra capacity would have to be capitalized and would not be considered routine repair work.

-

Unscheduled/Unplanned Maintenance — Requests for system or equipment repairs that - unlike preventive maintenance work - are unscheduled and unanticipated. Service calls generally are received when a system or component has failed and/or perceived to be working improperly. If the problem has created a hazard or involves an essential service, an emergency response may be necessary. Conversely, if the problem is not critical, a routine response is adequate. Reactive and/or emergency corrective work activities that occur in the current budget cycle or annual program. Activities may range from unplanned maintenance of a nuisance nature requiring low levels of skill for correction, to non-emergency tasks involving a moderate to major repair or correction requiring skilled labor, to emergency unscheduled work that requires immediate action to restore services, to remove problems that could interrupt activities, or to protect life and property.

Endnote

i The term building or facility will be used interchangeably to describe any built structure (buildings, dams, roadways, bridges, mass transit, etc.)