Overview

Within This Page

Preserving historic buildings is vital to understanding our nation's heritage. In addition, it is an environmentally responsible practice. By reusing existing buildings historic preservation is essentially a recycling program of 'historic' proportions. Existing buildings can often be inherently energy efficient through their use of natural ventilation attributes, durable materials, and spatial relationships. An immediate advantage of older buildings is that a building already exists; therefore energy is not necessary to demolish a building or create new building materials and the infrastructure may already be in place. Minor modifications can be made to adapt existing buildings to compatible new uses. Systems can be upgraded to meet modern building requirements and codes. This not only makes good economic sense, but preserves our legacy and is an inherently sustainable practice and an intrinsic component of whole building design. (See also Sustainable and Sustainable Historic Preservation.)

Realizing the need to protect America's cultural resources, Congress established the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) in 1966, which mandates the active use of historic buildings for public benefit and to preserve our national heritage. Cultural resources, as identified in the National Register of Historic Places, include buildings, archeological sites, structures, objects, and historic districts. The surrounding landscape is often an integral part of a historic property. Not only can significant archaeological remains be destroyed during the course of construction, but the landscape, designed or natural, may be irreparably damaged, and caution is advised whenever major physical intervention is required in an extant building or landscape. The Archaeological Resources Protection Act established the public mandate to protect these resources.

U.S. Courthouse at Union Station, Tacoma, Washington. Designed by the architectural firm of Reed and Stem and constructed in 1911 and renovated in 1987. Tall ceilings, generous daylight, and grand ceremonial spaces give historic buildings enduring investment value and make them attractive for a variety of uses.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration

James R. Browning U.S. Court of Appeals Building, San Francisco, California. Designed by James Knox Taylor in 1905 and rehabilitated in the early 1990's. Onsite surveys identify significant features to be retained as part of a comprehensive preservation plan.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration

Some practical and/or intangible benefits of historic preservation include:

- Retention of history and authenticity

- Commemorates the past

- Aesthetics: texture, craftsmanship, style

- Pedestrian/visitor appeal

- Contextual and human scale

- Increased commercial value (Economic Benefits)

- Materials and ornaments that are not affordable or readily available

- Durable, high quality materials (e.g., old growth wood)

Rehabilitated historic Congress Hall hotel, Cape May, New Jersey

Photo courtesy of the National Park Service and Congress Hall

- Retention of building materials (refer also to WBDG Sustainable Branch)

- Less construction and demolition debris

- Less hazardous material debris

- Less need for new materials

- Existing usable space—quicker occupancy

- Rehabilitation often costs less than new construction

- Reuse of infrastructure

- Energy savings

- No energy used for demolition

- No energy used for new construction

- Reuse of embodied energy in building materials and assemblies

Following passage of the NHPA, the Secretary of the Interior established Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties to promote and guide the responsible treatment of historic structures and to protect irreplaceable cultural resources. Today, the Standards are the guiding principles behind sensitive preservation design and practice in America.

- Apply the Preservation Process Successfully—The preservation process involves five basic steps: Identify, Investigate, Develop, Execute, and Educate. Successful preservation design requires early and frequent consultation with a variety of organizations and close collaboration among technical specialists, architects, owner/occupants, and preservation professionals.

Work on historic properties requires specialized skills. The Secretary of the Interior has identified professional qualification standards for a variety of preservation disciplines.

Four Treatment Approaches

Within the Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties there are Standards for four distinct approaches to the treatment of historic properties: preservation, rehabilitation, restoration, and reconstruction. These distinct approaches are presented from the least intervention to the most intervention.

Preservation focuses on the maintenance stabilization, and repair of existing historic materials and retention of a property's form as it has evolved over time.

Rehabilitation acknowledges the need to alter or add to a historic property to meet continuing or changing uses while retaining the property's historic character. This is the most commonly used and flexible standard for rehabilitation at a federal, state, and local level.

Restoration depicts a property at a particular period of time in its history, while removing evidence of other periods.

Reconstruction re-creates vanished or non-surviving portions of a property for interpretive purposes.

Alexander Hamilton Custom House, New York. Constructed 1899–1907 and renovated in 1994. Original drawings, photographs, and other archival documents are used to determine the original appearance of missing features to be replicated within restoration zones.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. General Services Administration

Guidelines for the Treatment of Cultural Landscapes such as landscapes, archaeological and maritime resources, sustainability, etc. are maintained by the National Park Service.

While each treatment has its own definition, they are interrelated. For example, one could "restore" missing features in a building that is being "rehabilitated." This means that if there is sufficient historical documentation on what was there originally, a decorative lighting fixture may be replicated or an absent front porch rebuilt, but the overall approach to work on the building falls under one specific treatment.

Treatment Plan

Determine the appropriate treatment for a historic property BEFORE work begins, at project initiation. This includes making sure that the proposed function for the historic property is compatible with the existing conditions in order to minimize destruction of the historic fabric. Generally, the least amount of change to the building's historic design and original architectural fabric is the preferred approach. To develop a treatment plan, site assessments are conducted to identify character-defining features and qualities. These assessments also examine the building or property as a whole to establish a hierarchy of significance, or "preservation zones," corresponding to specific treatments. "Zoning" establishes preservation priorities.

Of concern to preservation and design professionals is the cumulative effect of seemingly minor changes over time, which can greatly diminish the integrity of a historic building. Major preservation design goals include:

-

Update Building Systems Appropriately—Updating building systems in historic structures requires striking a balance between retaining original building features and accommodating new technologies and equipment. Building system updates require creativity to respect the original design and materials while meeting applicable codes and tenant needs.

-

Accommodate Life Safety and Security Needs—The accommodation of new functions, changes in technology, and improved standards of protection provide challenges to the reuse of historic buildings and sites. Designers must address life safety, seismic, and security issues in innovative ways that preserve historic sites, spaces and features.

-

Provide Accessibility for Historic Buildings—Accessibility and historic preservation strategies sometimes conflict with each other. Designers must provide access for persons with disabilities while meeting preservation goals.

-

Sustainable Historic Preservation—Historic preservation and sustainability goals overlap. So it is important to understand how to meet preservation and green building rating systems requirements to find creative and flexible solutions to reconcile differences.

-

Facility Use Policies, Building Design Standards, and Custodial Guidelines for Historic Properties—To ensure that both the long-term and temporary uses of the property are consistent with the long-term stewardship of the historic resource, implementing these policies, standards, and guidelines is essential.

Related Issues

Integrating Historic Preservation Concerns with Safety / Security Issues

We live and work in a changed environment: a world in which safety and security concerns have been elevated to their highest level since the founding of our nation. Preservation practitioners must now be concerned with the safety of an historic building's occupants, as well as the security of equipment and data. It is inevitable that the needs of historic preservation as established by the Secretary of the Interior will come into conflict with new federal guidelines and requirements for anti-terrorism force protection. For example, windows and fenestration details may be character-defining aspects intrinsic to an historic structure; however, it has become a universally-accepted fact that the majority of human injuries in an explosion are the direct result of exposure to high-velocity glass shards. Windows and openings in historic buildings that are vulnerable to possible terrorist activity may need to be reinforced to protect life and property. The US Army Corps of Engineers is performing experiments with various solutions to the problem of window glass failure in explosions and other terrorism-related activities. The need to meet safety and security requirements in historic buildings is critical when considering the necessary space between structures and public roads and parking areas. (See also WBDG: Accommodate Life Safety and Security Needs)

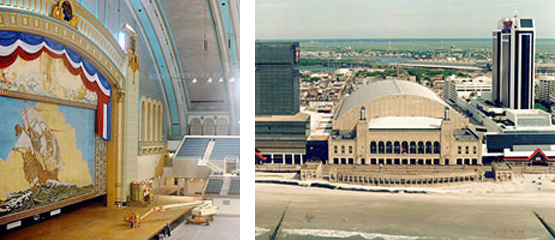

The historic Atlantic City Convention Hall in Atlantic City, New Jersey was built in 1926 and has many unique features including the large main hall and barrel vault ceiling with painted aluminum tiles decorated to resemble Roman bath tiles, A major restoration project was completed in 2001 and the project received the 2003 National Preservation Award.

Photos courtesy of the National Park Service.

Natural Disasters: Response, Recovery, and Resilience

After Hurricane Sandy, bus ads proclaimed New Jersey as "A State of Resilience."

Photo courtesy of NJ.com

The number and severity of natural disasters-hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, earthquakes, and uncontrolled wild fires—require special planning for historic properties. Many argue that the increase is due to climate change. In response, people are calling for resilience, the ability to withstand and bounce back from damaging effects of natural disasters, and to avoid or minimize them in future disasters. Federal, state, and local governments and private organizations are collaborating on the nation's response to climate change. This planning includes preservation of historic and cultural resources in immediate disaster response, long-term community recovery, and future mitigation efforts is an emerging issue.

In 2013, the United Nations issued a global report on Heritage and Resilience. It noted the connection between physical and social resilience. "The symbolism inherent in heritage is a powerful means to help victims recover from the psychological impact of disasters. In such situations, people search desperately for identity and self-esteem", and find it in reclaiming their heritage and historic places. It further stated, "Heritage contributes to social cohesion, sustainable development, and psychological well-being. Protecting heritage promotes resilience."

In the United States, the Secretary of the Interior's Standards provide guidance on protecting heritage and the treatment of historic areas and individual historic buildings. Applying the Standards can be a challenge in the rush of disaster response, or in the delicate balancing of life safety, economic and preservation values in long term recovery and planning. However, the result is worth the effort, and in some cases, like qualifying for government assistance, compliance with the Standards may be required. The guiding principle is to retain historic features while sensitively incorporating new features that reduce the risk of future damage from disasters. Sometimes, it's easy, like moving electrical service up out of flood-prone basements. Other times, difficult design challenges arise, like how to substantially elevate an historic house in a floodplain.

In some instances, the conversation about climate change, disaster mitigation, and adaptation includes the possibility of abandoning coastal or flood zones altogether. Human settlement often began and flourished in waterfront areas. Historic preservation concerns need to be considered when planning for the future of coastal and riverfront communities, many of which have extensive historic and prehistoric resources and valued traditional cultural patterns. Having an accurate, up-to-date inventory of historic resources and archeological sites (identified and predicted) in vulnerable areas is key to an informed and quick response when disasters strike, as well as a basis for long term resilience planning.

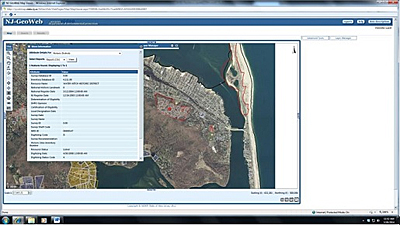

Working with FEMA after Hurricane Sandy, the New Jersey State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO) quickly surveyed affected neighborhoods to establish which ones were historic and which ones were not, allowing them to concentrate limited capacity and resources on historic areas, while eliminating review of the rest. By entering the data as a layer in the state's GIS (Geographic Information System) database, which contains a variety of environmental and social data, it became both a tool for recovery and for future planning. Computer mapping of future scenarios could visualize impacts to historic properties along with impacts to natural resources and human communities.

The Water Witch Historic District in Sea Bright, New Jersey, is bordered by red in the center of the image. To the right, is the Fort Hancock and Sandy Hook Proving Ground Historic District. Anyone can consult the NJ GIS system and choose data layers to "turn on", including Historic Districts and Historic Properties.

The National Park Service developed a manual on how to use GIS to document damage and plan for recovery, Historic Preservation Response Methodology .

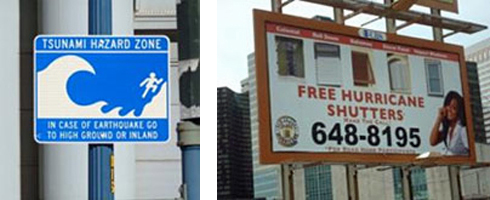

Warning sign on the San Francisco waterfront and New Orleans promoted hurricane shutters after Hurricane Katrina.

Photo Credits: U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD)

How can historic resources be protected against excessive wind, water, and/or vibration during disaster events? Physical modifications, elevation, seismic reinforcement, restoration, or creation of landscape features and operational procedures can address various threats.

The Mississippi Development Authority (MDA) and Mississippi Department of Archives and History (SHPO) developed guidelines for elevating buildings .

The National Park Service published "Preservation Brief 41: The Seismic Retrofit of Historic Buildings" .

A chimney with deteriorated mortar joints suffered vibration damage when an earthquake struck near Washington, D.C.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

Seismic upgrade of a former railroad car facility in Spokane, WA included horizontal metal strapping on long expanses of masonry. The rehabilitation project received historic tax credits.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

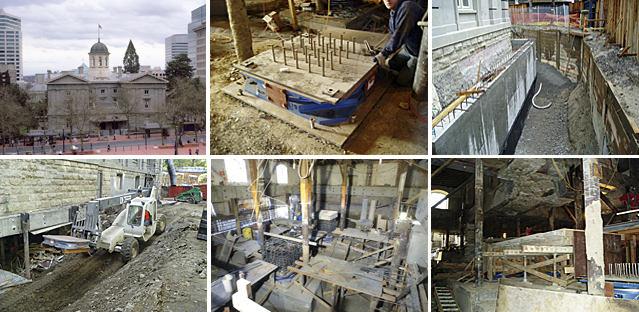

Pioneer Courage Courthouse in Portland, Oregon was built, beginning in 1869, and is the oldest federal building in the Pacific Northwest. The Courthouse underwent a seismic retrofit in 2005 using base isolation.

Top row left: Main exterior of the Courthouse. Photo Credit: Carol M. Highsmith.

Middle: Detail of base isolator. Photo Credit: GSA.

Right: The building raised to accept the base isolator. Photo Credit: GSA.

Bottom row left: Base isolator delivery showing elevated foundation and base isolator. Photo Credit: GSA.

Middle: Friction pendulums. Photo Credit: Sally Painter for GSA.

Right: Base isolation during construction.

Photo Credit: GSA.

In flooding scenarios, keeping water out of or moving out of an historic building are primary concerns. Flood gates or barriers help deflect incoming high water from entrances, basement windows, and cellar areaway doors. Sump pumps that operate on water system pressure and not electricity can keep performing when the power goes out. Berms, levees, and dunes can hold back or channel flood waters and/or tidal surges. Measures like relocating electrical service and fuel tanks out of basement areas can protect them from damage during flooding and allow a much quicker recovery after a disaster. And if building materials do get wet, it is important to recognize the inherent flood-resistance of some materials like mahogany trim or cypress flooring, and not unthinkingly rip them out and dispose of them.

The Yards: Southeast Federal Center (Washington Navy Yard Annex) Redevelopment

Public-private redevelopment of the fifty-three-acre former Navy Yard Annex property in Washington, D.C. brought to fruition a vibrant, mixed-use waterfront regeneration long envisioned by city planners and community activists. Acquired by GSA in 1960 to house federal offices, the property now encompasses 2,800 residential units, 1.8 million SF of office space and up to 400,000 SF of retail space and a riverfront public park, collectively known as The Yards.

Photo courtesy of Forest City Washington, now Brookfield Asset Management).

GSA worked closely with the Environmental Protection Agency to establish a process for what was expected to be a sizable remediation effort given the Navy Yard's prior use as an ordinance plant. Preliminary work included seawall stabilization undertaken in collaboration with the U.S. Coast Guard and hazmat remediation associated with street parcels, followed by soil remediation for development of individual lots. GSA coordinated removal of soil for cleansing with archeology testing & recovery along with careful removal of unexploded ordinance. This preliminary remediation enabled developer Forest City to proceed with new construction and rehabilitation of historic buildings.

Sustainable site features include subway station enhancements for safe access by mass transit, cycle tracks, Capital Bikeshare racks, greenspace, and solar energy. Phase 2 resilience measures include integration of landscaping and storm water management using native trees and planters designed to drain and filter water. Floating seabins intercept debris, pumping them through a filtered device to cleanse the Anacostia River of contaminated organic material.

The Yards Park, completed in 2010, was built through a public/private partnership between the GSA, the District of Columbia, and Forest City Washington. The 5.5 acre park was designed by M. Paul Friedberg and Partners and is managed by the Capitol Riverfront Business Improvement District (BID). GSA continues to maintain environmental remediation responsibility (soil, ACMs, lead paint) for entire site, while Brookfield Asset Management, which acquired Forest City Washington in 2010, oversees continuing redevelopment and site management.

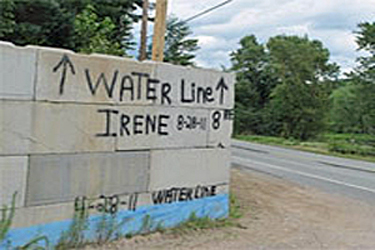

A roadside record of flooding from Hurricane Irene along the Ausable River in Ausable Forks, New York.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

This historic 1966 drive-in restaurant was completely inundated by floodwaters in Cedar Rapids, Iowa in 2008 and is currently undergoing rehabilitation. Recovering from a disaster can take years.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

Operational measures can also prevent flooding. In Montpelier, Vermont, after winter river ice started to thaw and break into chunks, it formed an ice dam under a bridge downstream and caused extensive water backup and flooding in the historic downtown. To prevent future recurrences, every winter, the city now stations a crane with a wrecking ball next to the bridge to break up the ice if another ice dam begins to form.

|

Historic Buildings and the National Flood insurance Program (NFIP) "The NFIP floodplain management requirements contain two provisions that are intended to provide relief for "historic structures" located in Special Flood Hazard Areas: |

Wildfire

Climate change is increasing the frequency and intensity of natural disasters and the risk of wildfire is no exception. A wildfire can be a serious natural disaster that spreads quickly over wooded areas and grasslands, endangering everything in its path. A wildfire can be a result of natural phenomena, escaped prescribed fires, an intentional or accidental human act, or a secondary impact of natural disasters such as earthquakes, drought, tornados, and hurricanes. For instance, the cracking of gas pipes can result in severe fires or an extended period of drought will significantly increase the risk for a wildfire. If one disaster isn't devastating enough, the secondary risk of fire brings an additional threat to areas that may not be in a position to adequately address them. Minimizing vegetative fuels and accumulated debris around a building removes potentially combustible materials.

A residential neighborhood in the aftermath of the 2018 wildfire in Santa Rosa, California.

Photo Credit: HUD

Wildfire can also affect ancient cultural resources like rock art. Heat from an intense fire can evaporate water in sandstone petroglyphs and lead to spalling of the rock face.

Battleship Rock Panel, Mesa Verde, Before and after the Chapin 5 Fire.

Photo Credit: National Park Service

Planning for Disaster

Protecting against fire hazards requires planning and can balance multiple priorities. While protecting life and property are first priority, the preservation of historic structures and cultural resources should also be incorporated into fire prevention and education programs. Communities and individuals will be better prepared to handle a fire disaster when there is a plan in place to do so.

A standard community baseline plan to protect life and property should include: evacuation routes and strategy, a gathering location, communication methods, assignment of roles and responsibilities. A response plan involving cultural resources and historic structures should be incorporated into more comprehensive community plans and involve input from local fire management officers and preservation and collections managers. Engaging multiple stakeholders will encourage a stronger response plan and recovery.

A general survey of historic properties and/or a material collection database is also necessary in order to understand where the risk is concentrated and what resources might be affected in a fire event. It is also important to note any known underground resources so that any ground disturbance during fire fighter activities can be minimized where possible in sensitive areas.

A plan should ensure there is adequate access to resources that may need to be protected in the event of fire. Such resources can be the physical resource itself (buildings, collections, etc.) as well as assets that offer aid such as fire extinguishers. A paper copy of the plan should also be produced in case electronic devices are down. Preventative measures can include placing archival collections in environments that are more resistant to fire, with proper temperature and humidity levels. Items such as rolling compact storage, flat files, modular basinets, and freezers can also protect resources from smoke and water damage. People who have responsibilities designated by a plan should regularly revisit their duties and hold practice drills.

Resilient Techniques to Protect Against Wildfire

There is a multitude of information that exists on fire code provisions and prevention strategies that protect human life and property. For information on incorporating resilient, protective measures to prevent fire within historic buildings, please see the section "Accommodate Life Safety and Security Needs". FEMA's "Wildfire Hazard Mitigation Handbook for Public Facilities" offers techniques to improve fire resistance, including fire-retardant roof assemblies to protect the part of a building most vulnerable to wildfire as firebrands, pieces of burning embers, are spread on prevailing winds. Some historic roof coverings like slate, tile and metal are non-combustible by nature and should be retained where possible.

Krasna Horka Castle

The Krasna Horka Castle was built on a hilltop in Slovakia in the 1300s and designated as a National Cultural Monument of the Slovak Republic. The castle was regarded as one of the country's best preserved castles. In 2012, a cigarette accidentally lit the grass below the castle on fire; this is often how wildfires begin. The fire quickly spread upwards due to high winds, ground vegetation, and low humidity and the castle was engulfed in flames, suffering extensive damage. The roof and the exhibition area in the gothic palace and the bell tower were completely destroyed.

A few simple measures could have made the castle more resilient to the fire. There were no adequate fire detection or suppression systems in place, nor was there easy access for fire fighters. Some simple fuel reduction techniques such as thinning out dense trees, removing underbrush, limbing trees, and prescribed burns could have suppressed the fire from spreading further up the hill and may have prevented any damage to the castle.

Krasna Horka Castle, Slovakia

Wildfire Suppression Systems

Fire Line Construction—Also called a "fire break", a fire line can suppress the spread of a wildfire by cutting off the supply of fuels that would allow the fire to build and spread. Usually a fire line is constructed using hand tools and needs to be between 6 inches and 3 feet wide. Heavy equipment may be used, but should be a last resort so that underground archeological resources are not disturbed. A fire line can also occur naturally, such as a river or canyon. Surrounding a neighborhood with a fire line can be an excellent preventive approach, before and during a wildfire.

Sometimes a preventative measure as simple as mowing the grass around a property can greatly reduce the risk of fire. Defendable space is created by reducing the grass and other fuels closely located to a structure thus limiting the ability for fire to spread. Restrictions may apply within local codes or recommendations on what types of material or landscaping is appropriate for use in residential areas.

Exterior sprinkler systems located on roofs and surrounding trees, poles, etc. can be extremely effective in protecting a structure against heat and ignition by flying wildfire embers. Placement of exterior sprinklers on historic buildings should be inconspicuous and sensitive to the structure. As a preparedness measure, FEMA will often fund grants for the placement of home sprinklers in wildfire prone areas.

Sprinkler System, Majestic Lakes, Minnesota. U.S. Forest Service Cabin

Certain historic building materials are naturally more resilient to fire. For instance, adobe structures, if well-constructed and maintained will resist damage from an external fire source. Mortared fieldstone, firebrick, cinder block, stone, metal, marble, slate, and ceramics are also resilient building materials. Certain fire and flame retardant coatings can be applied to flammable materials. They can be clear or colored, but should be used with caution as to not damage any historic features. An Intumescent paint coating may be applied to wood features and historic doors to improve resiliency and retain historic character. Intumescent paint applies like latex paint and appears only slightly thicker than latex paint. When exposed heat or fire, the coating bubbles and hardens into a charred surface thus creating an insulating protective barrier.

Scurvy Mountain Lookout Cabin, North Fork District, Idaho

Fire Wrap—Wrapping buildings has been a successful technique used by the National Park Service and the U.S. Forest Service to protect historic buildings from radiant heat and flying embers from nearby wildfires. The material used to wrap is similar to aluminum foil (aluminized glass fabric) but made from a flame retardant material. Similar to materials used to protect fire fighters as emergency shelters. The wraps are secured using staples and special tape to ensure that high winds of the wildfire will not peel away the protective coating. This shielding material is available commercially.

Relevant Codes and Standards

Federal Mandates

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 67 | "The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation"

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 68 | "The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for the Treatment of Historic Properties"

- Code of Federal Regulations, 36 CFR 61 | "Professional Qualifications for Historic Projects"

- Executive Order 11593, "Protection and Enhancement of the Cultural Environment"

- Executive Order 13006, "Locating Federal Agencies in Historic Buildings in Historic Districts in Our Central Cities"

- Executive Order 13287, "Preserve America"

- Executive Order 13834, "Efficient Federal Operations"

- National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) of 1966 as amended through 1992

- National Historic Lighthouse Preservation Act of 2000

For a list of other Federal Historic Preservation and cultural resource laws click here

Standards and Guidelines

- CALGreen

- NPS-28 Cultural Resource Management Guideline

- Guidelines for Federal Agency Responsibilities, Under Section 110 of the National Historic Preservation Act

- International Code Council

- NFPA 914 Code for Fire Protection of Historic Structures

- The Secretary of the Interior's Standards and Guidelines for Archeology and Historic Preservation (As amended and annotated by the National Park Service)

Additional Resources

Federal Agencies

- Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP)

- Department of Defense (DoD)

- DENIX Environmental Webpage

- Department of the Army

- AR 200-4 Cultural Resources Management

- Center of Expertise for Historic Structures and Buildings

- Tribal Nations Program by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- U.S. Army Environmental Command—Cultural Resources Management

- Department of the Navy

- Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command (NAVFAC)

- Historic and Archaeological Resources Protection Planning Guidelines, January 1997.

- Operational Navy Instruction (OPNAVINST) 5090.1D Chapter 13—Cultural Resources

- SECNAV 4000.35B Department of the Navy Cultural Resources Program

- Environmental Protection Agency

- Water, specifically climate change and water

- U.S. Air Force

- Department of Homeland Security

- FEMA Environmental Planning and Historic Preservation Program (EHP): The EHP program integrates the protection and enhancement of environmental, historic, and cultural resources into FEMA's mission, programs and activities; ensures that FEMA's activities and programs related to disaster response and recovery, hazard mitigation, and emergency preparedness comply with federal environmental and historic preservation laws and executive orders; and provides environmental and historic preservation technical assistance to FEMA staff, local, State and Federal partners, and grantees and sub-grantees.

- Department of Housing and Urban Development

- Guidance and technical assistance on historic preservation in HUD programs

- HUD Healthy Homes Initiative: Environmental hazards in the home harm millions of children each year. In 1999, in response to a Congressional Directive over concerns about child environmental health, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) launched its Healthy Homes Initiative (HHI) to protect children and their families from housing-related health and safety hazards.

- Department of the Interior—National Park Service

- Historic Preservation Services: helps our nation's citizens and communities identify, evaluate, protect, and preserve historic properties for future generations of Americans. Located in Washington, DC, the Division provides a broad range of products and services, financial assistance and incentives, educational guidance, and technical information in support of this mission. Its diverse partners include State Historic Preservation Offices, local governments, tribes, federal agencies, colleges, and nonprofit organizations.

- National Register of Historic Places: The National Register of Historic Places is the official list of the Nation's historic places worthy of preservation. The National Register is administered by the National Park Service, which is part of the U.S. Department of the Interior.

- Federal Preservation Institute (FPI): provides historic preservation news and information, with particular emphasis on information and training opportunities for Federal agency preservation officers, their staff, and contractors.

- Technical Preservation Services: The Federal Historic Preservation Tax Incentives program encourages private sector rehabilitation of historic buildings and is one of the nation's most successful and cost-effective community revitalization programs. It generates jobs and creates moderate and low-income housing in historic buildings.

- National Center for Preservation Technology and Training: NCPTT advances the application of science and technology to historic preservation. Working in the fields of archeology, architecture, landscape architecture and materials conservation, the Center accomplishes its mission through training, education, research, technology transfer and partnerships.

- National Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA): The National NAGPRA program assists the Secretary of the Interior with some of the Secretary's responsibilities under NAGPRA. Among its chief activities, National NAGPRA develops regulations and guidance for implementing NAGPRA; provides administrative and staff support for the NAGPRA Federal Advisory Review Committee; assists Indian tribes, Native Alaskan villages and corporations, Native Hawaiian organizations, museums, and Federal agencies with the NAGPRA process; provides consultation resources and other online databases; provides training; manages a grants program; investigates allegations of failure to comply; and makes program documents and publications available on the Web.

- The Secretary of the Interior's Standards for Rehabilitation and Illustrated Guidelines on Sustainability for Rehabilitating Historic Buildings

- Department of Transportation—Historic Preservation: The FHWA Historic Preservation and Archeology Program provides guidance and technical assistance to Federal, State, and local government staff regarding these Federal laws, as well as regulations, executive orders, policy, procedures, and training on topics related to historic preservation and cultural resources. The Environmental Review Toolkit provides information geared to the Federal-aid highway program and its related projects. Information includes guidance, recommendations, and successful practices to help address historic preservation/cultural resource issues during the transportation project planning and development process.

- Department of Veterans Affairs—Historic Preservation: The Office of Construction & Facilities Management (CFM) provides design, major construction, and lease project management, design and construction standards, and historic preservation services and expertise to the Department of Veterans Affairs to deliver high quality and cost effective facilities in support of our Nation's veterans.

- U.S. General Services Administration (GSA)—Historic Preservation: GSA's historic preservation program provides technical and strategic expertise to promote the viability, reuse, and integrity of historic buildings GSA owns, leases, and has the opportunity to acquire.

- "Restoring a Treasure: U.S. Custom House, New Orleans"—GSA Film on New Orleans Custom House/response to flood

- Historic Buildings Preservation Tools and Resources

- Technical Preservation Guidelines

- U.S. Marine Corps

Organizations/Associations

- The Association for Preservation Technology International (APTI)

- National Conference of State Historic Preservation Officers (NCSHPO)

- National Trust for Historic Preservation

- National Preservation Institute

- Smithsonian Institution—Architectural History and Historic Preservation (AHHP)

Publications

- AIA Disaster Assistance Handbook by The American Institute of Architects. Washington, DC: AIA, May 9, 2017.

- Climate Change And Cultural Heritage Conservation: A Literature Review by Ann D. Horowitz, Maria F. Lopez, Susan M. Ross and Jennifer A. Sparenberg. APT Technical Committee on Sustainable Preservation's Education and Research focus group, June 30, 2016.

- Federal Historic Preservation Laws by the National Park Service. 2006.

- Fire Prevention and Building Code Compliance for Historic Buildings: A Field Guide prepared by the University of Vermont Graduate Program in Historic Prevention in cooperation with the Vermont Division for Historic Preservation and the Vermont Department of Labor and Industry, December 1997.

- Wildfire Fire: Fireline Construction by NPS Fire and Aviation Management. Web. July 1, 2016.

- Fire Protection in Historical Buildings and Museums by Siemens Switzerland Ltd, Building Technologies Division, 2015. Web. July 1, 2016.

- Fire Safety in Historic Buildings by Jack Watts, National Trust for Historic Preservation, June 2008.

- Mesa Verde: Archeology and Fire by National Park Service. 2007.

- Preservation Brief 41: The Seismic Retrofit of Historic Buildings by the National Park Service. 1997 Web. April, 2016.

- Report Examines Effectiveness of Outdoor Sprinkler Systems During Wildfires by Bill Gabbert, Wildfire Today, 2010. Web. July 1, 2016.

- Talking About Disaster, Guide for Standard Messages by National Disaster Education Coalition. 2004. Web. July 1, 2016.

- The Use of Intumescent Paint to Provide Passive Fire Protection to Heritage Buildings by Heritage Council of New South Wales. 2012. Web. July 1, 2016.

Training

- Historic Preservation courses in WBDG continuing education

- EPA Climate Change Adaptation Training courses: Designed to illustrate how our climate is changing, what services will be affected, and how to strengthen our climate resiliency.

Others

- Building Research Information Knowledgebase—Historic Preservation (BRIK)—an interactive portal offering online access to peer-reviewed research projects and case studies in all facets of building, from predesign, design, and construction through occupancy and reuse.

- Building Technology Heritage Library

- PreservationDirectory.com—an online resource for historic preservation, building restoration and cultural resource management in the United States & Canada.